Gathering, MELK Galleri, September 2020

Gathering, a video piece by Andreas Bennin

Camera Rosten, ten photographic contact prints by Ole John Aandal

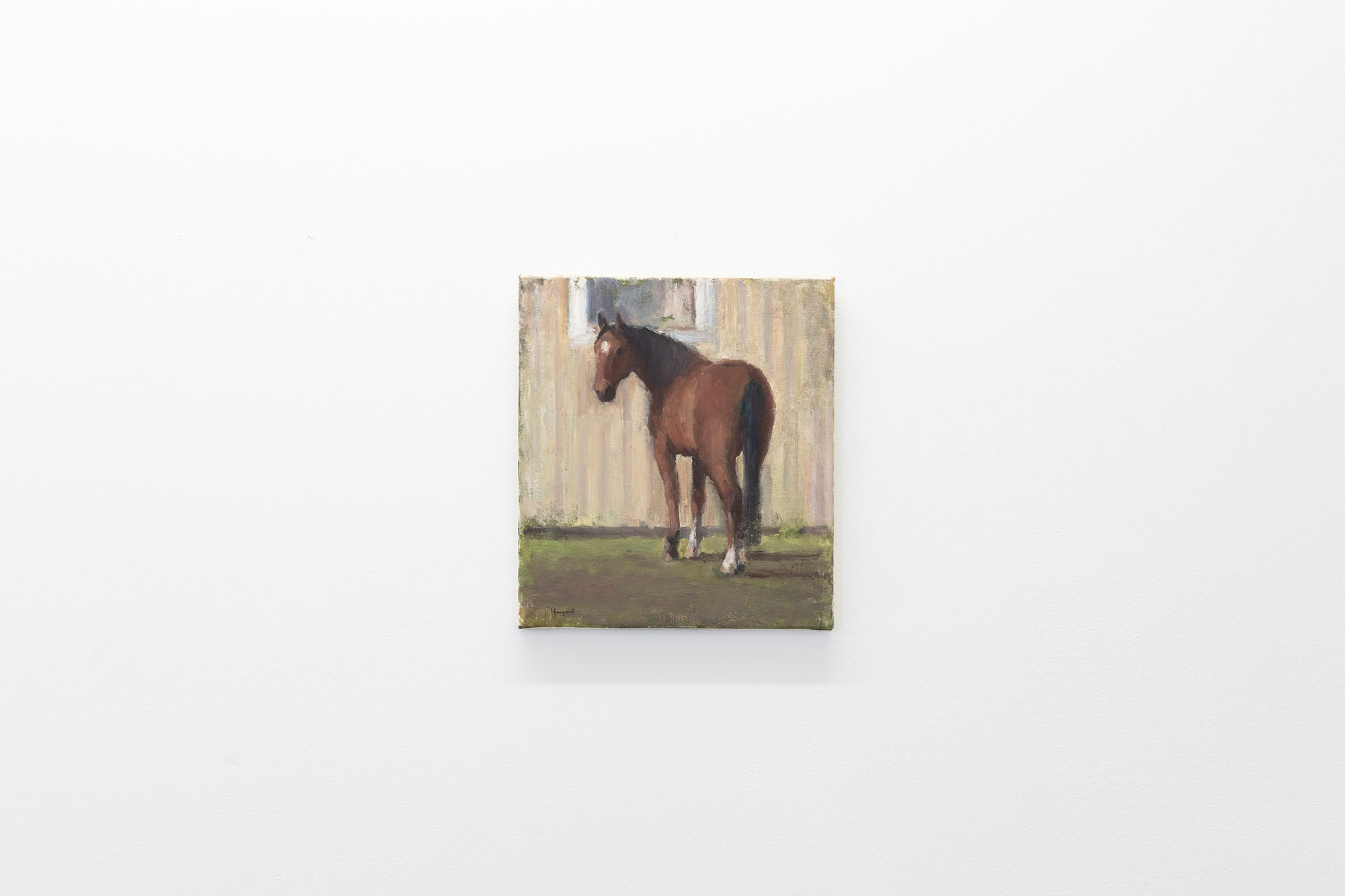

Hesteblikk, a painting by Halvard Haugerud

and a vintage print by Tom Sandberg.

Brought together by Morten Andenæs

Earlier this summer, and quite by chance, I found myself at the site of Ole John Aandal’s photographs of the upper reaches of Gudbrandsdalslågen, one of Norway’s most spectacular rivers. Just a few years back they dammed the wildest parts of it up and no one had given a damn he commented laconically, and since this particular part of the river had never been fixed to paper, Aandal decided to build a camera from an old coffee tin, climb down into the gorge and capture the water as it gushed downstream that final summer. The 8×10 inch contact prints from his Camera Rosten project, developed on site and now on view at MELK Gallery, are the only images that remain of this once wild riverbed.

Standing above the dam that day, on the shore of what was now a serene, manmade lake, it occurred to me that Aandal could have saved himself a lot of trouble and peril if he’d chosen to make use of a drone. Perched safely on the riverbank, he could have generated some stunning, immersive imagery, allowing us to dive downstream with the currents, the river splashing about us on all sides, and then perhaps with a swoop, our belly tingling, we’d be whisked up and away to soar like a majestic bird, the river a silvery snake slithering through the landscape far below.

We’ve seen those images before. An eye in the sky, or the gaze in the cockpit as Annie Ernaux calls it, freed from the constraints of the body; free to roam and gather information, impressions, an overview; to deliver images, packages for amazon, or bombs.

Less spectacular, but no less immersive, Andreas Bennin’s video-piece Gathering takes us into an unnamed forest through the lens of a drone. At certain points during its journey the machine nearly falls to the ground, then rises again. It moves forwards, then stops, hovering and rotating with mechanical precision aimed at emulating the smoothness of human vision, but a little too precise really, to come across as natural.

Bennin’s drone is an eye in a forest, roaming around a landscape that seems to expand in every direction with a strangely suffocating sameness. There is no end in sight.

Aptly then, I gather is a way of saying “as far as I understand” or “as far as I can see”. Quite literally, the limits to my horizon. Is Bennin’s drone in the business of seeing? I seem to see through it. Like tele-vision. A sense of presence where I’m absent.

When Merleau Ponty said of the medical gaze that it was marked by curiosity, but without the duty of appreciation, he could have been talking about drones. Seeing is more than watching, and looking. I watch Netflix, I look at the apples on the table. I cannot claim to always see you.

Photographic contact prints of a river, and drone imagery stored on a disk of a forest. The figure of a horse, meticulously applied to canvas over time by Halvard Haugerud, and wilting sunflowers captured in a 60th of a second on the living-room floor by Tom Sandberg. Time, space, and light. Alchemy, transformation. The horse and flowers bring to mind the thousands of floral and animal images I’ve pointed to and seen since I was a small child, attending to picture books with my parents, but they also, immediately, provide us with the illusion of recognition. Though we desperately long to make an impression, to be looked at and watched, we need to be seen and recognised rather than merely registered. In a book I’ve read and re-read a bunch of times I found a spot I had underlined, but that obviously took an nth reading before being absorbed. In our faces my heart, brief as photos John Berger said of poetry that it listens, that it acknowledges an experience which cries out.

The four artists here see, and listen. Their works describe the world, absorb it, rather than traffic in metaphor. The river flows The flower wilts The horse turns The forest…

The four artists here fumble. They gather impressions and leave an impression. Gut reactions and chemical prints stained with images; the things of this world literally touching it as it develops; to borrow an expression from Elaine Scarry, there is a certain presentness to the works on display, like the experience of pain. The water that envelops the sharp rocks of the riverbed like a layer of skin in Aandal’s photographs, water that was later to be harnessed to power up devices and bank accounts near and far was also used to dilute the developer and fixer necessary for calling forth the images themselves; drops of water now returned to the sea and out of sight still present within the image. Just like the trappings of hair and dead skin from Tom Sandberg’s home and person that are now an inherent part of the image and represented in the print as blank spots makes it pressingly clear that he is no longer amongst us, the water, now downstream and out of sight is present in the image as absence.

Once we gathered things necessary for our survival. The gathering itself a way of coming together in the service of community; the bringing together of food, thoughts or company, of jointly attending to each other and our surroundings, etching our way into each other’s lives to create bodies of knowledge. Like Aandal’s choosing to get his hands wet, the imprint of a lover’s hand on your face after sleep or the smell of fish on my breath in the morning, it is the risky business of proximity that generates worlds. And though it would be easier to let go, to rid oneself of the burden of closeness and thrive in absence, it is not necessarily better.

Morten Andenæs, 2020